The Tao of Landscape Photography is about the recovery and the illumination of the path to creativity. I say recovery because the way of the Tao is also a recognition that the path was always there. Along our long way we have acquired various forms of learning and knowledge that have helped us grow not only as individuals but also as landscape and nature photographers. But this learning and knowledge has also helped to restrict our awareness of nature. The Tao of Landscape Photography is about rekindling some spontaneity that brings back a more child-like sense of wonder and unrestricted awareness. This leads to a new awakening as we move away from well known formulas and instead experience and photograph the natural landscape with the eyes of a child.

In this post I will discuss what is the Tao and introduce two key source texts, The Tao Te Ching and Chuang Zu. I will then use direct passages from these source texts translated into English to explore eight Taoist ideas and how they relate to Landscape and Nature Photography in our own time: (1) Return to Nature; (2) Negative Space; (3) Yin and Yang; (4) Flow “Wu Wei”; (5) The Simple Life is the Best Life; (6) Perception: Is this Life a Dream?; (7) Reality is a Seamless Whole; and (8) Self Understanding.

What is Tao?

The Chinese word Tao means “the way”. One might ask what kind of way? First and foremost, it is the way of nature including our own nature. It is also the way of harmony with others and the way of self understanding. Taoism is the study of the way. Its origins trace back to the philosopher-hermits, called Xian, who roamed the mountains of ancient China. It comes as no surprise that the Chinese ancient pictogram for Xian (僊) represents a person in the Mountains (1). Although Taoism eventually developed into a religion complete with rites, rituals, and practices including meditation, Feng Shui and Tai Chi; in this blog post I am primarily interested in Taoism as a philosophy that sheds some light on my own relationship with nature and how nature provides inspiration for all of my photographs. In this regard I stay close to the original source texts for Taoism where one actually finds very little about religious rites, rituals, and practices.

For me Taosim is part of what Aldous Huxley calls the Perennial Philosophy (2). This is a perspective views all of the world’s spiritual traditions as pointing to a common truth. In this regard I have found echos of Taoism with its emphasis on a direct, immediate and intuitive experience of nature as the way in both Zen Buddhism and American Transcendentalism. It should not be surprising that one sees similarities of Taoism in Zen because the practice of Zen came to an already Taoist China by way of India and only later moved to Japan and eventually the West. Zen’s exposure to Taosim helped transform Zen into the spiritual practice that we know today. For more on Zen and its relation to Taoism and Photography see my post: The Way of Zen, Love of Nature and Photography. The similarity with American Transcendentalism is purely coincidental and there is no known evidence that either Emerson or Thoreau had access to any Taoist writings. To me this is actually a good thing because it demonstrates that the teachings of Tao need not be tied to a specific historical and cultural tradition and are relevant in all times and places including our own time. For more on Thoreau see my post: Journey to Your Own Walden Pond.

Ancient Writings

Although there are many ancient texts on Taoism, there are two primary texts that have informed my understanding of Taoism

1. Tao Te Ching (The Book of the Way) attributed to Lao Tzu 2. The Inner Chapters attributed to Chuang Tzu

The Tao Te Ching is generally regarded as the central text of Taoism (3). It was written in the 5th Century BCE. Although it is attributed to the sage Lao Tzu, we do not know for sure if such a person even existed and most scholars believe it was compiled by several authors. The book is rather short consisting 81 brief chapters and only 5000 Chinese Characters. Perhaps as a testimony of the difficulty of translating the Tao Te Ching, it has been translated into English by more different translators than any book other than the Bible. Each Chinese Character in the Tao Te Ching has a very nuanced meaning making a precise English Translation virtually impossible.

The Chuang Tzu is named for its primary author, Master Chuang. Composed in the 4th or 3rd century BCE, the Chuang Tzu also focuses on the person of Lao Tzu, who is presented as one of Chuang-Tzu’s own teachers (4). Although both the Tao Te Ching and Chuang Tzu’s writing are paradoxical in nature, in Chuang Tzu the paradoxes rise to level where they are often humorous and perhaps also a bit irreverent. Many of the chapters come in the form of parables and stories. But one cannot fully appreciate or even understand Chuang Tzu without first reading the Tao Te Ching. So if you choose to read the Chuang Tzu Inner Chapters (it is short and makes great bed-time reading!), make sure you also have close at hand the Tao Te Ching!

(1) Return to Nature

A central theme in the Taoist perspective is a return to nature. At a more personal level this also means a recovery of our own nature. I say recovery, because our own original nature, a sort of childlike primordial state, was always there. Taoism points to several factors that stand in the away of awareness of our true nature. Chief among them is our contemporary culture that surrounds us and other trappings of society. Society convinces us as we grow up that the path to both success and meaning involve the acquisition of material wealth along with work accomplishments and recognition. Unfortunately this path according to Taoism also leads us further and further away from nature. What we need instead is a return to a life more anchored in spontaneity, passion and intuition.

Taoism is also deeply suspicious of both language and thought. Our words, thoughts and concepts can literally never describe our experience of nature. The first words of the Ta Te Ching are “The Tao that can be spoken of is not the real way.” Taoism always emphasizes the importance of direct experience. In this regard a landscape image that best reflects our direct experience of nature is also one that is in a more natural alignment with the Tao.

Chapter One of the Tao Te Ching: What is the Tao? Translated by Sam Tarode

The Tao that can be spoken of is not the real way. That which can be named is only transient. The nameless was there before the sky and the earth were born. The named is the mother of the ten thousand things. In nothingness you will see its wonders; In things you will see its boundaries. These two come from the same origin, although they have different names. They emerged from somewhere deep and mysterious. This deep and mysterious place Is the gateway to all wonders.

This passage introduces the heart of the Taoist perspective. The Tao, or the way of nature, cannot be named. Any attempt to do so is transient, bound not only to a particular moment in time, but also to a particular person. Words cease to be relevant the moment they are uttered and are not to be confused with the Tao itself. Chuang Tzu put this more humorously when he said “A dog is not considered a good dog because he is a good barker and a man is not considered a good man because he is a good talker!” In the Tao there are no boundaries and limits, but in our attempts to describe our experience using conceptual thought we establish just that, boundaries and limits. Does that mean we should abandon our attempts to name and describe our experience? Certainly not, but be aware that the mystery and wonder of Tao and nature is ultimately beyond any kind of logical description.

In this next passage Lao Tzu likens the Tao to the spirit of Perennial spring linking the Tao to nature itself and to what the poet Dylan Thomas alluded to when he wrote in his poem Fern Hill, ” a force that drives through a green fuse a flower.

Chapter 6 of the Tao Te Ching: The Source, Translated by Sam Torode

The Spirit of the Perennial spring is said to be immortal. She is called the Mysterious One. The Mysterious One is the source of the universe. She is continually, endlessly giving forth life, without effort.

The spirit of the Perennial spring is the source of all that is . Some may refer to the Perennial spring as mother nature and she continuously brings forward life. She is also mystery. In the best of our nature and landscape photographs we share glimpses of this mystery of the spirit of perennial spring. But neither our images or words can unravel the mystery. At best we can evoke in our images and words some of the spirit of the mystery of the perennial spring. For more on Mystery see my post Mystery: The Holy Grail of Landscape Photography.

As previously mentioned, The Tao Te Ching likens the return to the more spontaneous rhythms of the natural world to a recovery of our child-like nature. Consider this next passage.

Chapter 55 of the Tao Te Ching: Become Childlike, Translated by Sam Torode

The virtuous are like innocent children--- poisonous insects will not seize them, wild beasts will not seize them, birds of prey will not attack them. Their bones may be weak, and their muscles tender, but their grasp is sure. They know nothing of power, yet they are bursting with life. Their spirits are strong indeed! They can sob and cry all day without becoming hoarse; their voices are harmonious, indeed! To know this harmony is to know the eternal. To Know the eternal is to know enlightenment. To increase life is to know blessedness. To increase inner vitality is to gain strength. As creatures grow and mature, they begin to decay. This is the opposite of the Tao---- the Tao remains ever young.

As a metaphor, the child represents the eternal beginning and the ever springing source of all life. To some the notion of returning to the innocence of our youth may seem overly idealistic and for most of us just not practical. But the message here is that as we grow and mature we move gradually out of harmony with the rhythms of nature that are second nature to the child. This movement away from the rhythms of nature takes us also away from the Tao and our inner vitality and strength. This sets the stage for rigidity and ultimately decay. This is so unlike the child who is flexible, growing, and open to all the world. The child may have no awareness of self and is part and partial of the flow of everything which surrounds him/her. The child lives and breathes in the Tao. How would your your life change if every day you greeted the new morning with the eyes of the child? In Landscape Photography, how would your approach to the landscape and the wonder of nature change if every day you approached life with the eyes of the child-with no restricted awareness, being genuinely open to whatever comes your way?

2. Negative Space

Chapter 11 of the Tao Te Ching: Negative Space, Translated by Sam Tarode

A wheel may have thirty spokes, but its usefulness lies in the empty hub. A jar is formed from clay, but its usefulness lies in the empty center. A room is made from four walls, but its usefulness lies in the space between. Matter is necessary to give form, but the value of reality lies in its immateriality. Everything that lives has a physical body, but the value of a life is measured by the soul.

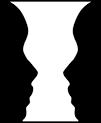

For most of us, when we approach a beautiful landscape, we immediately start picking out subjects against a background. In doing this we are experiencing nature and the landscape as discrete and separate parts. The Taoist perspective, however, informs us that this process of picking out and naming subjects in the landscape may actually be getting in the way of us experiencing the true nature of reality, in other words experiencing nature and the landscape as a seamless whole. Many of you will recall this image that is often used to help shed some light on figure ground relationships and the potential for confusion or misrepresentation.

In this image you will likely first see a couple of silhouetted faces facing each other. But on second glance you will see that the image is also of a vase. The Taoist perspective will take this even a step further and place importance on paying attention first to the background and the negative space. Without the background and negative space no subject or subjects can have any form. “A wheel may have thirty spokes, but its usefulness lies in the empty hub” and “the room is made of four walls, but its usefulness lies in the space between”. When a Taoist first approaches a mountain landscape, he/she is likely to first notice the valley below and the sky above rather than the imposing mountain looming as a primary subject. Focusing first on the negative space and background can go along way toward transforming how we view nature and the landscape and it is my belief that this will be for the better. This helps move us away from our habitual way of viewing the world, glorifying certain objects in the landscape, rather than experiencing what every landscape actually is, an integrated whole. Focusing on the negative, brings us back to a more primordial and intuitive way of experiencing the world, it brings us back to the source of all that is, it brings us back to the eternal Tao.

The use of negative space is especially apparent in the long tradition of Chinese landscape paintings. The painting above is by artist Ma Yuan active from c 1190-122. Ma Yaun was a leading artist at the Southern Song painting academy in Hangzhou. His painting titled Scholar by a Waterfall, shows a gentleman in a mountainous garden like setting with the wind sculpted and somewhat jagged rhythms of the pine tree contrasting with the quiet mood of the scholar, and both are looking out into the flowing water of the cascading river and the emptiness beyond. Notice the considerable amount of negative space enveloping all parts of the image. The use of negative space is a consistent feature of Chinese Landscape Painting, where space, emptiness and the void are inseparable from forms, with each depending upon the other. It is out of the Tao and negative space that forms emerge. A recognized authority, Wucius Wong, on Chinese landscape painting in his book, The Tao of Chinese Landscape Painting (9) puts it this way:

“Truth, to the artist, is both mass and void, both the material world and the artist as he fuses himself completely with his subject mater. Void (negative space) is hsu, the opposite of shih (mass/forms), and is generally considered by artists as more important than mass in painting.”

3. Yin an Yang

Chapter 42: Yin and Yang, Translated by Sam Tarode

The Tao produces unity; unity produces duality; duality produces trinity: trinity produces all things. All things contain both the negative principle (yin) and the positive principle (yang). The third principle, energetic vitality (chi), makes them harmonious.

Yin Yang is the principle of natural and complementary forces and patterns that depend on one another and do not make sense on their own. The original meaning of yin and yang is associated with the dark north facing and light south facing sides of a mountain. These two sides of the mountain are of course inseparable as all mountains have north and south facing sides and one side, be it the light or the dark side, will always imply the existence of the other. We cannot have light without dark, or dark without light. Although Yin and Yang are often thought of as as feminine and masculine forces and it certainly includes these two, Yin and Yang encompass just about everything that we think about and experience in the natural world.

Yin and Yang are opposites that fit seamlessly together made harmonious through the flow of natural vital energy called “Chi”. The yin yang concept is not the same as Western dualism, because the two opposites are not at war, but in harmony. Yin and Yang are a unity. One cannot have the Yin without the Yang! This is often difficult for the Western mind to grasp, because we are accustomed to thinking that good is better than bad and that ultimately good should triumph. But Taoism teaches “When everyone knows good as goodness, there is already evil” and “When everyone knows beauty as beautiful, there is already ugliness” (Tao Te Ching, Chapter Two). At this point it will be helpful to hearken back to this popular ancient symbol of the Yin and Yang.

The dark area contains a spot of light, and vice versa, and the two opposites are intertwined and bound together within the unifying circle. Yin and yang are not static, the balance ebbs and flows between them – this is implied in the flowing curve where they meet. Yin contains some of the Yang and Yang some of the Yin. This applies to ourselves as well as the natural world. Yin and Yang forces are in each one of us in a constant ebb and flow. Likewise Yin and Yang are in the natural landscape in a constant ebb and flow of light and shadow, negative space giving rise to form, high and low, near and far, soft and hard, chaos and order, permanence and impermanence, life and death, feminine and masculine. The Taoist photographer will bring the forces of Yin and Yang present in the landscape and themselves into a harmonious ebb and flow in their photographic creations, mirroring the natural world that is after all a reflection of the Tao.

4. Flow “Wu Wei”

Chapter Thirty Two: Where to Stop, Translated by J H McDonald

The Tao is nameless and unchanging. Although it appears insignificant, nothing in the world can contain it. If a ruler abides by its principles, then her people will willingly follow. Heaven would then reign on earth, like sweet rain falling on paradise. People would have no need for laws, because the law would be written on their hearts. Naming is a necessity for order, but naming cannot order all things. Naming often makes things impersonal, so we should know when naming should end. Knowing when to stop naming, you can avoid the pitfall it brings. All things end in the Tao just as the small streams and the largest rivers flow through valleys to the sea.

One of the enduring symbols of the Tao Te Ching and Taoist literature in general is flowing water. Water, like the Tao flows naturally, easily moving around, under, over, or through obstacles without resistance from stream, to river, to sea. This Taoist notion of flow is also known as “Wu Wei” or effortless action. It is not the same as inaction or passivity, but rather going about life in a simple and flowing manner, not trying to force things, but instead living in tune with the rhythms of nature. In his landmark book, Tao-The Watercourse Way (6), Alan Watts said this about Wu Wei: “The art of life is more like navigation than warfare, for what is important is to understand the winds, the tides, the currents, the seasons, and the principles of growth and decay, so that one’s actions may use them and not fight them.”

This notion of Wu Wei and going with rather than against the flow of course also applies to vocations including the practice of nature and landscape photography. This is not to say we go out into the field without any intentions or expectations. Although some photographers claim this is what they do, I think at this point this is somewhat of a platitude. Of course we have some intentions and expectations. We are not literally flowing into nature and the landscape at random. At a minimum we have made a choice of when and where to go. What is important is that once we are at our choice of location we are navigating freely with the vicissitudes of nature–not trying to fight it when nature does not cooperate with our expectations. We move more freely with acceptance and a minimum effort cooperating with the ebb and flow of nature.

5. The Best Life is the Simple Life

Ancient Masters, Chapter 15, Translated by J H McDonald

The Sages of old were profound and knew the ways of subtlety and discernment. Their wisdom is beyond our comprehension. Because their knowledge was so far superior I can only give a poor description. They were careful as someone crossing an frozen stream in winter. Alert as if surrounded on all sides by the enemy. Courteous as a guest. Fluid as melting ice. Whole as an uncarved block of wood. Receptive as a valley. Turbid as muddied water. Who can be still until their mud settles and the water is cleared by itself? Can you remain tranquil until right action occurs by itself? The Master doesn’t seek fulfillment. For only those who are not full are able to be used which brings the feeling of completeness.

In this passage, Lao Tse talks about the qualities of the sages of old who were examples of living a life in harmony with the Tao. Although these sages were alert, careful, courteous, and fluid as melting ice; they also were likened to the image of an “uncarved block.” The metaphor of the uncarved block” is one of the most enduring and frequently found metaphors in all of Taoist literature. The uncarved block represents nature in its original, unchanged, and natural form. Benjamin Hoff, in the Tao of Pooh, writes “The essence of the Uncarved Block is that things in their original simplicity contain their own natural power, power that is easily spoiled and lost when that simplicity is changed (7)”. This fits in well with the Taoist emphasis on negation and the importance of negative space. Living a life of the sage is not so much about cultivation of various practices such as mindfullness meditation and the like, as it is about the stripping away of much of the baggage we have collected in the process of fitting in with society and getting back to a much simpler and spontaneous life close to nature. The paradox is that when we return to the uncarved block we also unlock our potential to live a more fulfilling and meaningful life. An uncarved block has the potential to be transformed into something extraordinary and worthwhile. But this will only happen when one moves with rather than against the rhythms of nature. In the words of Lao Tsu: “Who can be still until their mud settles and the mud is cleared by itself, Can you remain tranquil until right action occurs by itself?”

As a landscape photographer I have found that return to the “uncarved block” is also the best way to grow in the art and craft of photography. Nature after all is what my photography is about, so would not it make sense that living life flowing with rather than against the currents of nature would best support my creative endeavors? Even the creation of good imagery has more to do with pairing down, stripping away, removing distractions, and getting back to a simpler more elemental state of elegance than it does with introducing layers upon layers of additional elements and complexity. Less is more and I have found for me at least simpler is better.

6. Perception: Is this Life a Dream?

Chuang Tzu Chapter Two, Verse 24 , The Butterfly

“Long ago, a certain Chuang Tzu dreamt he was a butterfly— a butterfly fluttering here and there on a whim, happy and carefree, knowing nothing of Chuang Tzu. Then all of a sudden he woke to find that he was, beyond all doubt, Chuang Tzu. Who knows if it was Chuang Tzu dreaming a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming Chuang Tzu? Chuang Tzu and butterfly: clearly there’s a difference. This is called the transformation of things.”

In this often quoted passage, the philosopher Chuang Tsu dreams that he is a butterfly fluttering about, moving around from here to there wild and free. When he awakens, however, he is utterly confused. He does not know if he was a butterfly dreaming of Chuang Tsu or if he was Chuang Tsu dreaming he was a butterfly. From the perspective of the Tao our perception of our individual self or ego, as something separate from nature and the environment that surrounds us, is in itself a kind of dream or illusion. Whether he is Chuang Tsu or a butterfly in a way does not even matter. What matters is that all of us live life in accordance with the rhythms of nature.

This story provides a beautiful visual image that most of us can instantly relate to that illustrates the Taoist point that distinctions, such as butterflies, us as individuals, reality, dreams—are all just projections. In a sense we live in a dream world all of the time. When I see two butterflies, I am seeing my own perception of two butterflies. The butterflies are not literally in my mind. Experience never puts us in direct contact with reality (5).

As a Landscape and Nature photographer, this story of the the butterfly is especially dear to my heart and I believe it will also be to many of you. How often have you gone into the field with camera and had the feeling that you are part and partial with everything that surrounds you: the air you breath, the trees in the forest, the flowers at the lakes shore, and the birds flying overhead? For many of us this is also the moment where we transcend our individual self and live more in the spirit of Wu-Wei. We move about with effortless action and seemingly unbridled creativity because we are in harmony with the rhythms of nature. We do not resist but rather embrace what nature has in store for us this day, whether it be rain falling in the forest, a glorious sunset, or merely another overcast day.

In the middle of a hot 2020 August, I started my long loop trip hike into the Goat Rocks at sunrise and did not finish until well after sunset. I suppose I could have finished sooner, but what is the hurry? In the evening I passed through this happy meadow just below a ridge top and decided just to hang out and enjoy nature at her finest for an hour or so. Hiking down from the ridge to the car I eventually had to use a headlamp and in order to not surprise animals I played Neil Young music through my JBL speaker attached to my belt. No sooner than I set up the headlamp and music I peered out onto the trail about 50 feet ahead and saw two narrowly spaced bright eyes staring at me. At first I thought it a person because the eyes were fairly high off the ground. Then I saw a big and long bushy tail. It could have been a wild dog or a cat, I do really know for sure. The animal would not move so I turned up the music a bit more , now Neil Young’s Natural Beauty Song. The animal then slowly with grace, almost like our family cat Precious, started moving up the rock talus and then perched onto a flat rock and sat down like a royal cat still looking at me. Amazingly calm I proceeded back out onto the trail but it later occurred to me that if this was a cat it may have just positioned itself in prance position. Nevertheless it was all ok and good—Perhaps thanks to some mellow Neil Young music! One reader of this story mentioned to me that this perhaps this cat was my spirit animal. This got me thinking about Chuang Tzu and the butterfly story. Perhaps I was this cat staring back at Erwin Buske?! But then again I the cat or the cat as I may not matter. What matters is that we are both in the flow of the Tao, fluttering about our way in harmony with the rhythms of nature.

7. Reality is a Seamless Whole

Those Who Divide Cannot See, Chapter 17 of the Chuang Tzu, Translated by David Hinton

“A sage inquires into realms beyond time and space, but never talks about them. A sage talks about realms within time and space, but never explains. In the Spring and Autumn Annals, where it tells about ancient emperors, it says the sage explains but never divides. Hence in difference there is no difference, and in division there’s no division. You ask how this can be? The sage embraces it all. Everyone else divides things, and uses one to reveal the other. Therefore I say: “Those who divide things cannot see.”

In this verse Chuang Tzu speaks of the sage as someone who focuses on the whole of nature, not dividing nature into its constituent parts. The very act of dividing the world into specific objects of this and that can prevent us from truly seeing: “Those who divide things cannot see”. Although Chuang Tzu had no awareness of Gestalt , the influence of Taoist thought is evident in Gestalt including the Gestalt Principles established by its founder Kurt Koffka and the Gestalt Psychology of Fritz Pearls. Gestalt refers to a configuration or pattern of elements so unified as a whole that it cannot be described merely as a sum of its parts. This complements beautifully the Taoist perspective of nature.

As mentioned earlier, the Taoist does not immediately focus on picking out the subject from the background. Attention is first on the background and the associated negative space and only then on the forms that emerge from the background. But the Taoist does not view these forms as discrete stand-alone parts but as part of an integrated whole, in other words as a Gestalt.

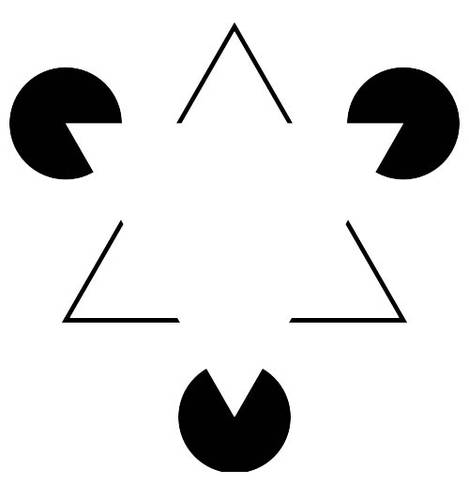

The Gestalt Principles include: (1) Similarity –Objects and elements including shapes and patterns that are similar are perceived as a group; (2) Proximity–The eye perceives that objects close to one another as belonging to a group; (3) Continuation–the mind sees lines and curves as continuing even if visual information is missing or there are objects in the way; and (4) Closure– The mind completes shapes that only exist partially in the image, such as a partial circle or triangle.

The kanizsa Triangle shown above has often been used by Gestalt psychologists to demonstrate the principle of closure, which maintains we see objects grouped together as whole even when they are incomplete. In the Kanizsa Triangle we see two triangles and three circles even though technically there are no complete circles and triangles in the image, only three pac-men and several incomplete triangles. Our holistic vision completes the gaps in the shapes. This image challenges the reductionist approach to vision that what we see in a image is merely the sum of its parts. We actually perceive objects/subjects that from a purely objective point of view are not even there. This is similar to the Taoist perspective that councils us to pay attention to the background and negative space as much as the figures and the subjects. Both Gestalt and Taoism challenge our limited way of viewing the world that focuses on discrete objects. Both Gestalt and Taoism challenge us to see a world holistically rather than just the sum of its parts.

Some gestalt principles that bring unity to a landscape scene can be seen in the above image titled Autumn Passage. There is a similarity of shapes between the granite rock in the foreground, the upper half of Valhalla, and the top of Lichtenberg peak in the upper left. The proximity of the granite rock with the harmoniously colored sections of golden yellow green and orange red foliage helps form a unified foreground group. The triangular granite rock partially hidden by foliage (closure) points (continuation) down the slope to the lake and peak aided by slightly diagonal lines in the mid ground. The lake itself and the peak point to the sky and warm clouds of sunset (continuation). For more on Gestalt and Landscape Photography, see my blog post: Transcendental Nature Photography: Creating Inspiring Images with Lasting Impact.

As a landscape and Nature photographer I have always thought that presenting my image as well balanced and integrated consistent with my experience in nature is more important than forcing all attention onto a subject. When I see some popular landscape images today the single minded focus on the subject often seems aggressively forced as if the photographer is screaming for our attention. Backgrounds are heavily darkened and directional light is manipulated to the point where the contrast between the subject and background is so strong as to seem unnatural. Some of this may be done to get instant attention on social media where people judge your image in a second or two then move on. This is not the way of the Tao. The Taoist perspective is more about turning down the contrast and volume, focusing first on the background, revealing the often subtle path of light, and creating a well integrated and balanced image where the rhythm and flow of the landscape is presented manner that seems as natural as nature itself.

The Taoist notion of the world is that it is organic and changing in never ending cycles of growth, decay and renewal. The world is an organism where every little thing is related to everything else. In this world there are no truly lone actors, and reality is a seamless whole. In this sense Taoism foreshadows the views of the modern environmental movement. For more on the Environmental Movement see my blog post–“Landscape Photography: Inspiration, Preservation, Conservation and the Environmental Movement.”

8. Self Understanding

Chapter Forty Seven: Explore Within, Translated by Sam Tarode

Without going abroad, you can have knowledge of the world. Without gazing at the stars, you can perceive the heavenly Tao. The more you wander, the less you know. The wise explore without traveling, discern without seeing, Finish without striving, and arrive at their destination, without leaving home.

In this passage we hear echoes of Thoreau’s message of Walden’s Pond. Thoreau found self understanding at Walden Pond within close walking distance of his original home in Concorde, Massachusetts. For more on Walden’s Pond see my blog post: Journey to Your Own Walden Pond: Thoreau’s Legacy and Message to a Modern World. The path of self understanding need not involve going outside of where we are at in the here and now. Travels to distant parts of the earth are not necessary. This is because as we travel in the spirit of the Tao we realize the entire world is also within us. Alan Watts put it this way: “We have been brought up to experience ourselves as isolated centers of awareness and action, placed in a world that is not us, that is foreign, alien, other—which we confront. Whereas, in fact, the way an ecologist describes human behavior is an action: what you do is what the whole universe is doing at the place you call the here and now. You are something the whole universe is doing in the same way that a wave is something that the whole ocean is doing.” We are part and partial of the world. The idea of ourselves as separate from the world from the Taoist perspective is an illusion. For more on living an authentic life close to nature see my post Finding Your Photographic Vision and the Search for the Authentic Self.

In Taoism, self understanding is paradoxically related to freedom from a sense of self. Self cultivation involves more a stripping away of various ideas and behaviors we have acquired along the way to help us dominate and control what we perceive to be the external world than it involves adding anything new. The stripping away involves: (1) Surrender–the recognition that ultimately our ego is not in control, (2) Wu-Wei or effortless action–going with the flow in a manner that recognizes there is no separation between our self and the world: (3) Simplicity-the recognition that we can best experience our connection to nature when we live a simple life, free from the weight of excessive possessions and vain pursuits of fame and glory, (4) Grounding–living our life close to the rhythms of nature and the earth, (5) Humility–living an authentic life with integrity that recognizes the limits of our individual self and the corresponding recognition that we are part of something much greater than our individual self, (6) Spontaneity–a return to our more child-like sense of wonder and playful experience of the natural world.

The recent covid pandemic brought home to me this idea that we can arrive at our destination without leaving home. The pandemic, especially initially, placed limitations on my movement and for a few months I took images of only places within walking distance of my home. I began to realize now more than ever how much that goes into creating imagery is drawn from internal sources of inspiration. When I or yourself take an image of a landscape close to our homes, it is not just what is out there, it is also our emotions and passions of a moment in time that are coloring our perception of what is out there. Our internal world can be beautiful and when the photographer integrates the internal and external worlds through an image this is a manifestation of the all inclusive Tao— it is also the art and craft of photography. What might otherwise seem ordinary and mundane receives the inspiration of the life force of the Tao and now seems uniquely attractive and aesthetically interesting, worthy of sharing through the creation of photographic art. For more on the pandemic and landscape photography see my post: Growing Creatively during a Global Pandemic. For more on Sources of Inspiration including Internal Sources see my post on Sources of Inspiration.

Conclusion

There is no time better than here and now to embrace the eternal Tao and the freedom it offers to rekindle a sense of child like wonder, to bring back unrestricted awareness, to experience nature and landscape with fresh eyes and to reflect this experience in our nature and landscape photography. Now is the time to experience the “Watercourse Way”, move in the spirit of Wu Wei, and bring forward your image of the uncarved block. In the words of the late great motivational speaker Wayne Dyer, “Do the Tao Now (8).”!

Erwin Buske Photography (c) 2020

Thanks for reading this blog post. I invite everyone to share with me their reactions to this blog post on The Tao and Landscape Photography. I would love to hear your comments and thoughts on this article. If you think others would be interested in this post, please share it with your friends and other acquaintances. If you like the kind of content I am creating on this blog please let me know and consider subscribing to blog. Thanks again and may the Tao of nature be with you!

References and Additional Resources

(1) Taoism: Essential Teaching of the Way and it Power, 1999, Allan Cohen, Audio Book (2) The Perennial Philosophy, Aldous Huxley, 1945 (3) Tao Te Ching, The Book of the Way, Translated by Sam Tarode, 2013 (4) Chuang Tzu, Inner Chapters, Translated by David Hinton, 2014 (5) The Meaning of Life: Perspectives from the World's Great Intellectual Traditions, Great Courses, Jay Garfield, 2013 (6) Tao, The Watercourse Way, Alan Watts, 1975 (7) The Tao of Pooh. Benjamin Hoff, 1983 (8) Change Your Thoughts, Change Your Life, Living the Wisdom of the Tao, Dr. Wayne Dyer, 2009 (9) The Tao of Chinese Landscape Painting, Wucius Wong, 1991

Thank you 🙏🏻

☮️

LikeLike

Your’e welcome!

LikeLike

Erwin, first time I have seen your work, or even heard of you. I’ll be sure to finish reading this blog and I am anxious to see more of your wonderful photography. A friend sent me this post and I’m grateful to him and for the content.

LikeLike

Thanks John! I hope you enjoy the post and it does reflect a lot of where I am currently at in my photographic and life journey.

LikeLike

Mesmerising picture😍

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

🙂

LikeLike

Lovely photos and wonderful area.

LikeLike

Thank you, both for this comprehensive post and for sharing your great photos. Taoism chimes with me, and I have read a fair number of the texts you reference here too. Will follow your continuing journey (and pop back to see where you’ve been on it so far too).

LikeLike

Thanks Bear! I am glad you enjoyed the post. The Tao, Nature and Landscape Photography to me fit together so well!

LikeLike